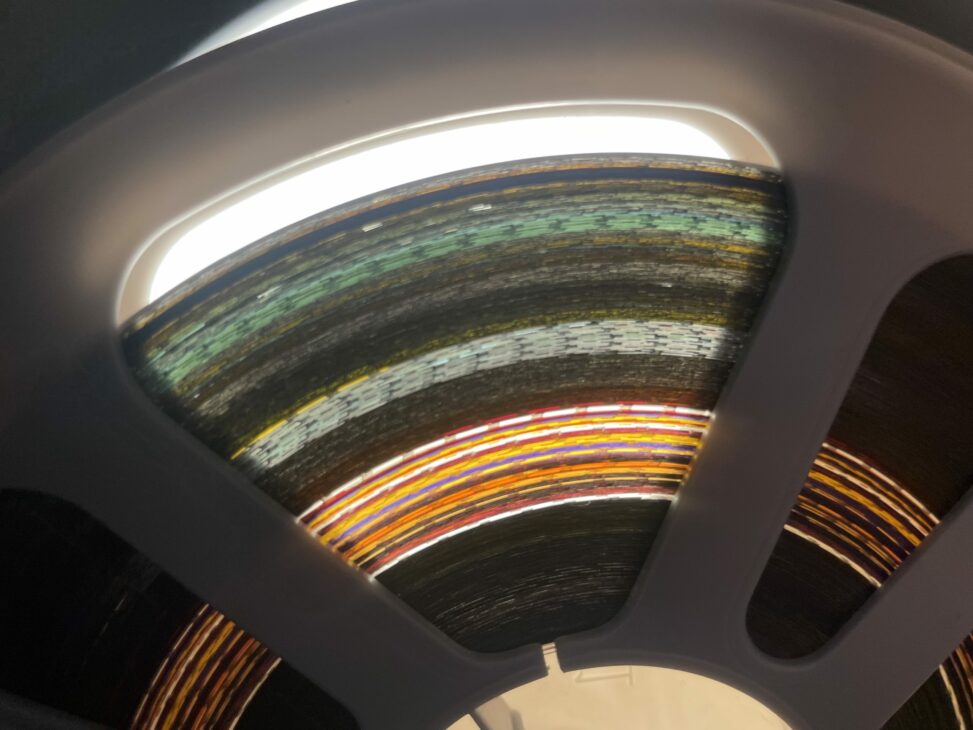

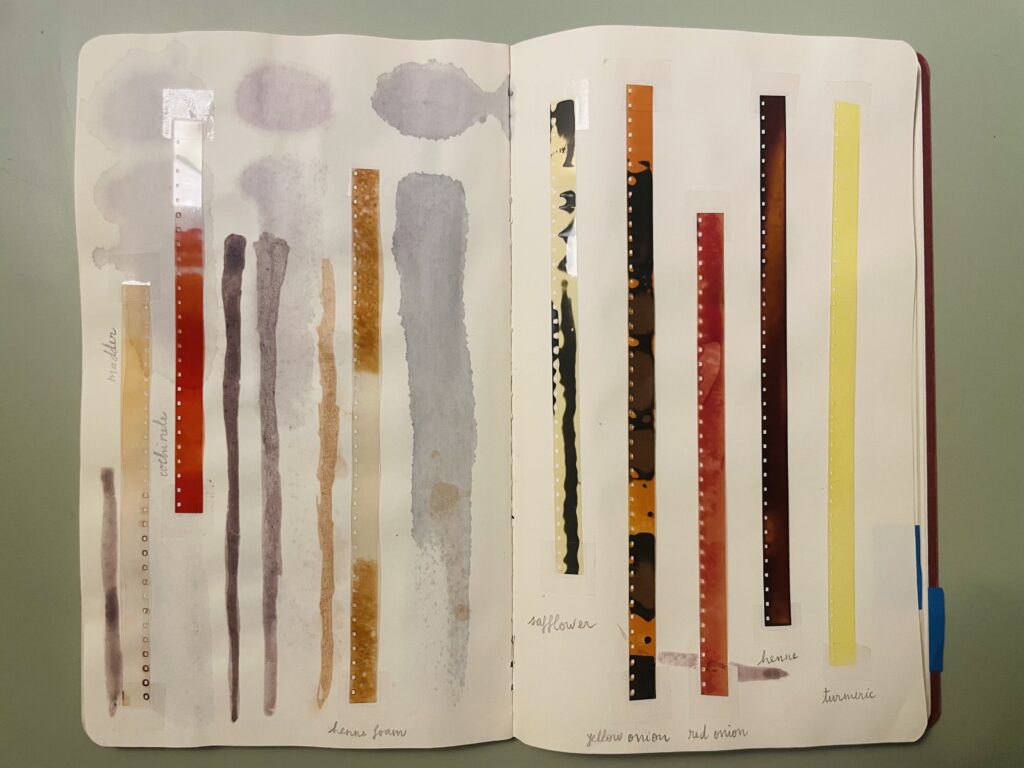

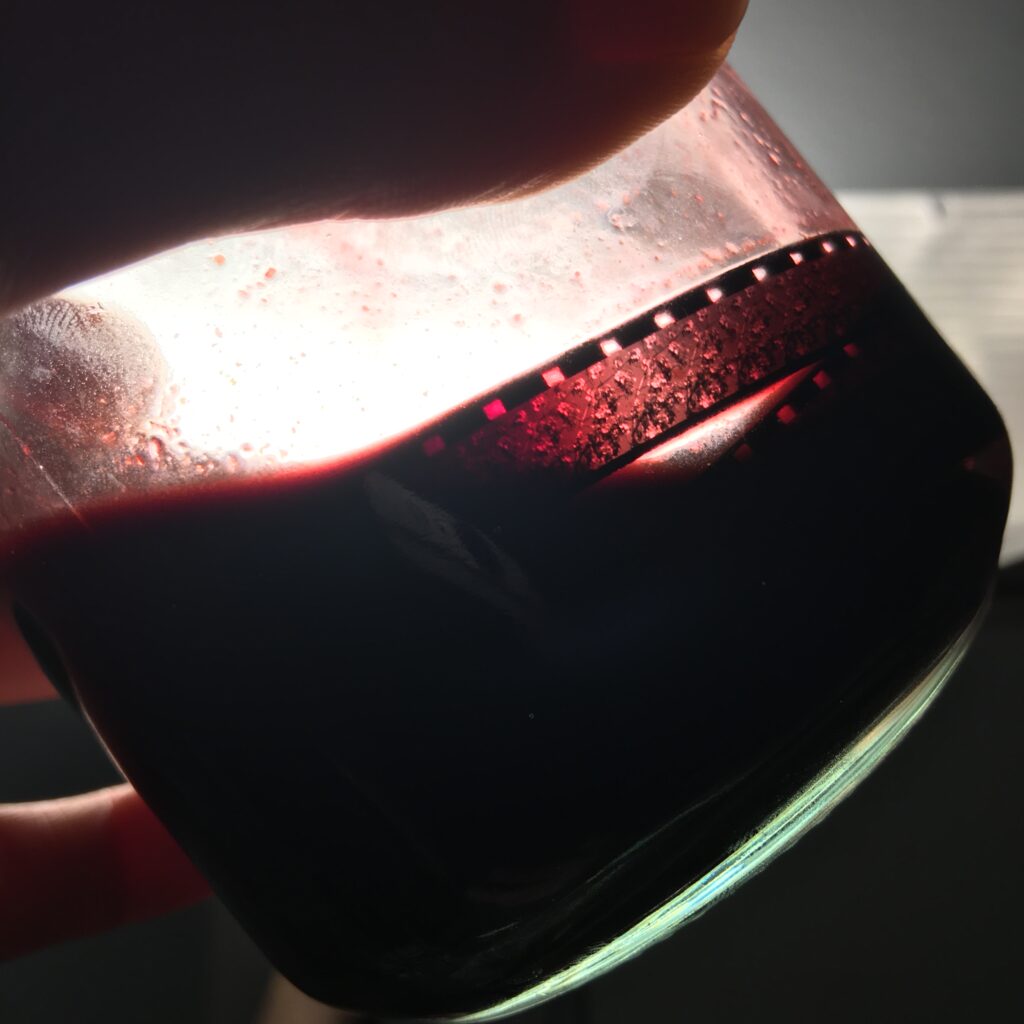

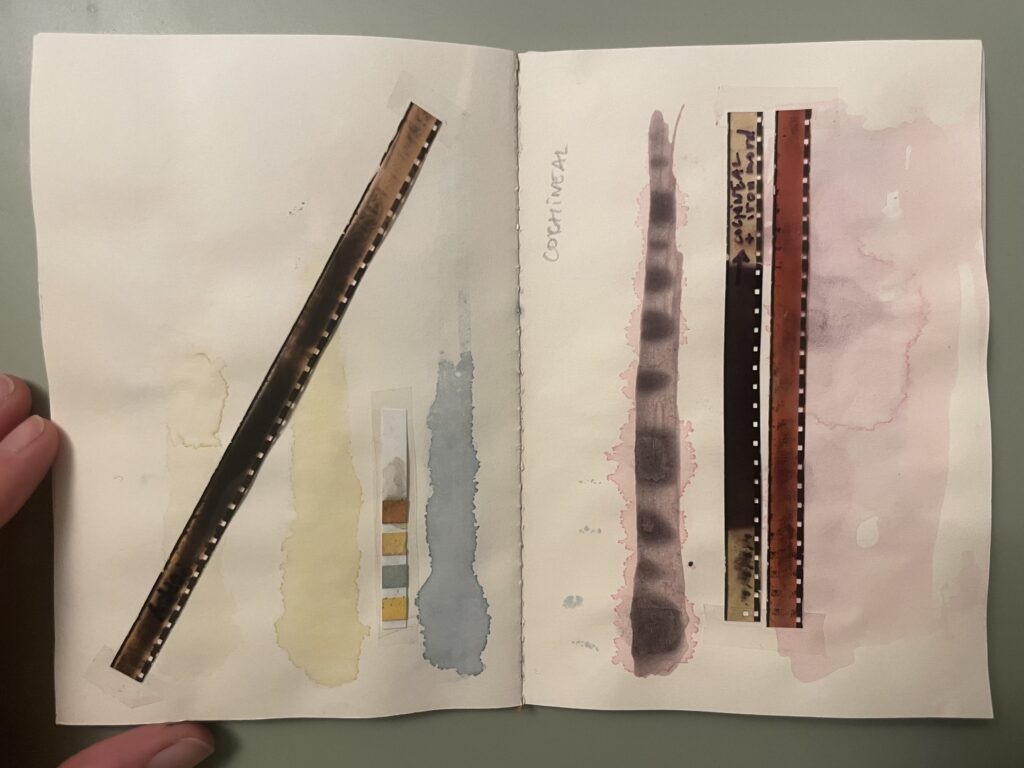

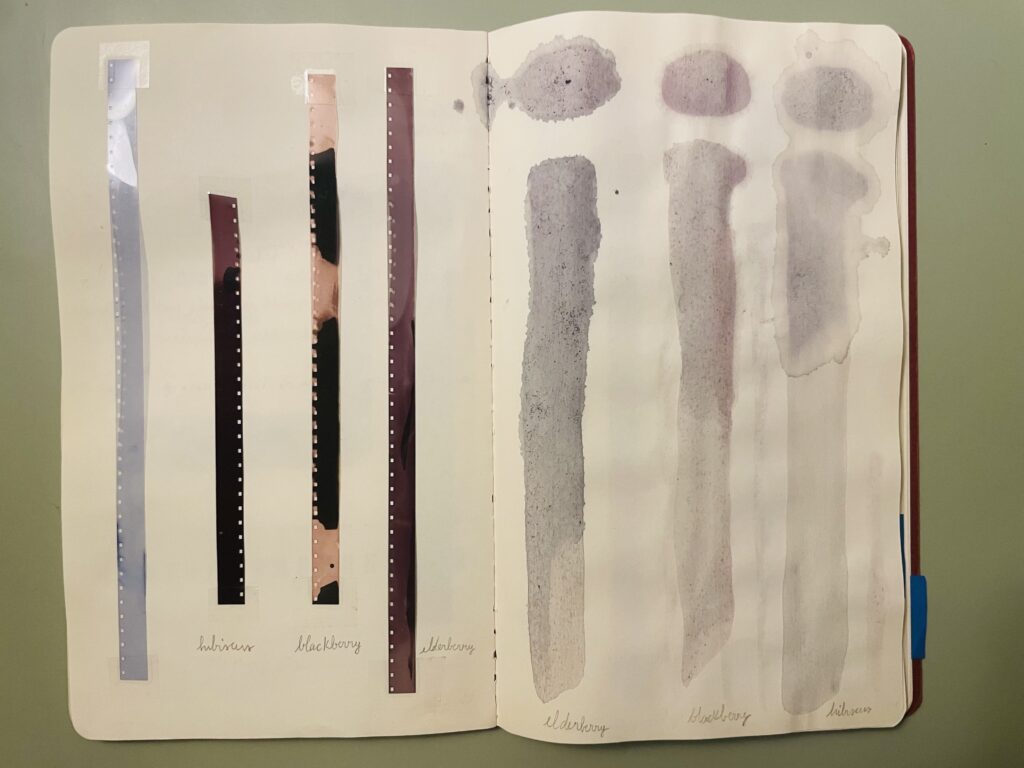

Unnatural Colour looks at processes for tinting and toning photo-chemical film using organic materials to explore, both conceptually and materially, the relation between representing a landscape and directly using its natural elements in the process of creating an image while conveying elements of its historical and material context.

Ongoing research & technical training with:

Teresa Castro https://www.culturgest.pt/en/media/cinema-razao-ecologia-microsite/

Esther Urlus & Filmwerplaats Lab https://filmwerkplaats.hotglue.me/

Jeniffer Lienhard https://appleoakfibreworks.com/

Project Supported by The Arts Council of Ireland (2024-2025) and Culture Moves Europe 2025

Thanks to Paul Read, Barbara Flückiger filmcolors.org, and Eye Film Museum International Conference: The Colour Fantastic Revisited: Across Global Histories, Theories, Aesthetics, and Archives https://www.eyefilm.nl/en/programme/this-is-film-2025/1390550

“In 1918, William van Doren Kelley, the inventor of several commercial natural colour processes, (…) complained that he had several times been attracted to a ‘theatre’ where ‘color films’ were advertised only to find that the subjects were merely ‘black and white hand-colored films’. Kelley proposed that only films ‘photographed so that the colors are selected entirely by optical and mechanical means and reproduced again in a like manner’ be called ‘natural color motion pictures’. ‘Color motion pictures’ he described with his accustomed sarcasm as ‘films arbitrarily colored with dyes … to suit the individual taste’. He clearly implied that tinting or toning was not natural. He was not the first to want to distinguish between ‘real’ colour films that reproduced the original colours in a scene and ‘arbitrarily’ tinted, toned or stencilled black-and-white films.” (P. Read, 2009).